ARTIST INTERVIEW: SYLVIA RADFORD

Please introduce yourself. What originally sparked your interest in becoming an artist?

Hi, I’m Sylvia and I’m an emerging artist based in Chichester, West Sussex. Well, I’ve been interested in the creative arts since I can remember. My father, a keen amateur photographer, collected Life Magazine and I was captivated by these photographic images of contemporary history. Growing up in rural Malaysia, I was initially homeschooled through the Parent’s National Education Union (PNEU), who produced the loveliest education books, one of which was a collection of plates of artworks. Van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters and Constable’s The Hay Wain have stayed with me, evocations of ways of past lives.

I was constantly drawing, even with chalk on our concrete driveway! Part of my fondness for drawing, was it provided a space to build my own world and to be a narrator of my imagination. I aspired to be a creator of some sort, but I chose a different path, ending up in civil engineering specialising in the spatial planning, design and implementation of urban transport around the UK, Middle East, and Asia, a career I enjoyed and loved!

Working in Singapore in 2012, I became friends with a wonderfully generous Australian painter Astrid Dahl, who reignited my interest to become an artist. I was instinctively drawn to the material language of painting and exploring the possibilities of expression and meaning. However, it wasn’t until I developed a critical illness that I decided to refocus my energies. I embarked on an art education route offered through West Dean College which is just up the road from me, completing a foundation in 2017, a diploma in 2020, and recently graduated (2024) with a Masters in Fine Art.

Your work explores identity and is often informed by childhood memories. How have you explored your own identity as a British-Singaporean?

Born in Thailand of British and Singaporean heritage, by the time I was 14, I had lived in 13 different places across seven countries around Southeast Asia, the Middle East and the UK. Our identity and perception of home or belonging is influenced by our experiences in life. The concept of home gives us a sense of our place in the world, an identity. Yet home can feel a foreign place for people positioned between different cultural identities who often must negotiate cultural dislocation to find a sense of belonging and identity. I am currently interested in the work of Sasha Gordon, a Polish Korean artist living in NY who explores themes of race and identity throughout her paintings, and she says: ‘being Korean and Polish was always a strange concept for me because I felt as though I’m forced to identify more with one than another’.

Rather than an interrogation of my specific British and Singaporean heritage, I meditate on notions of cultural belonging/unbelonging, questioning dislocation to deal with each new situation. In this context, translating memories of my childhood experiences continue to occupy my practice. I am interested in an ambivalent notion of disconnection - about not quite existing without a clear indication of who one is - and its tension with ideas of home and belonging that constitute the shifting identity. The children in my paintings are about growth and resilience through changing and sometimes destructive circumstances, about not being eradicated because one feels constantly ‘unhomed’, although one’s identity has moved on.

How do you portray the fragility of memory in your work?

I work on notions of childhood memories being fragile and unreliable records of fleeting moments and remnants of the past. Childhood photographs, symbols of our history and connections, are likewise selectively captured. I draw on my memories and an archive of family photographs from my childhood, nurturing abstractions of memories of being in a certain frame of mind towards a feeling of belonging in the past that can be used to give vitality to the present.

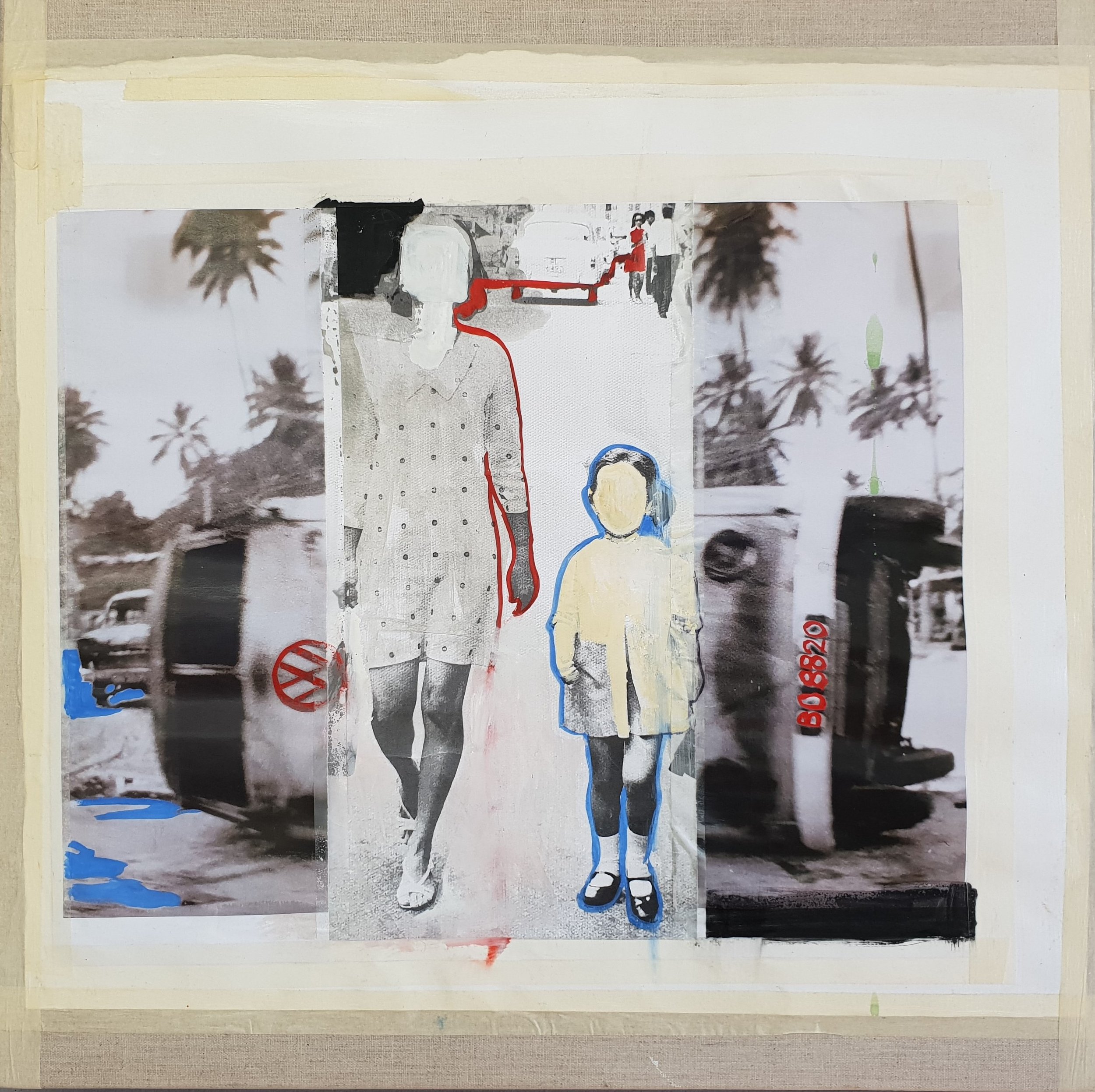

I aim to present the ephemerality of memory and an atmosphere of instability or unreliability in the image presented. I experiment with how I mash up different components, how I blur or sharpen edges, make use of complex superimpositions, transparent layering, and so on, so that the work captures the fleeting strangeness and unreliability of childhood memory. I sometimes build the work up as if in fragments like the way billboards of films used to be hand painted and then torn off for the next picture, but you still might have glimpses of the history.

I adopt motifs such as erasure, masking and trompe l’oeil, suggesting that these images and hence experiences are only remembered in part and conflated, foregrounding the fragile nature of memory, its erosion and fabrication. I also break up the picture plane, engaging with an interplay between naturalism and abstraction to express the slippages and contradictions around the illusory nature of childhood memory and cultural ambivalence.

Arguably though sometimes the work is most successful in this regard when bold changes happen organically – for example where figures have been selectively, and spontaneously, painted out or whitewashed or where representation has been left consciously incomplete or unresolved!

Why do you find people fascinating to paint? Why do you choose to leave out/ blur facial features? Is there a reason you prefer to paint groups of people instead of just one individual on their own?

Portraying interactions between people excites me, and my work investigates the complexity of relationships, often through female subjects. I explore the effects of instabilities and conflict in cultural and family relationships and the effects on childhood. These ideas are both personal and universal and it is about how families identify with each other across cultures, how families respond to or are disassociated from each other across cultures and across time. My work may have specific narrative to me, but it’s about opening it up to other people to make their connections.

Through making the image more obscure, or blurred, I’m exploring notions of unreliable memory, as well as examining contexts concerning cultural position, gender and identity and what one is prepared to reveal. If the face is more abstracted, does that further distance us from the understanding of the persons whose images we are representing and trying to understand? I also feel the effectiveness of portraying an eerie or uncanny atmosphere can be greater the stranger and looser the approach is in the treatment of my figures and their faces, especially when the result is unpredictable, eerie or uncanny. I’m trying to capture more immediacy and freedom in the painting.

Describe your creative process from start to finish of your most recent painting. What initially inspired the composition?

I usually work on more than one painting at a time, maybe two, three or four. Past Imperfect came about as part of a body of work over the past 18 months, that took a single photograph as its starting point. I have returned to that image to reframe and deconstruct it in several ways. Sometimes I stall on one painting, put it to one side in the studio, like in the case with Past Imperfect, and only returned to it a year later.

I am fascinated by the relationship between photography and painting for several reasons and it is an important part of my creative process. Photography connects people to their own personal history, and this is where my journey has been. By using photographs as a source material and working in series, my work becomes distanced from their source materials. In this way, I feel liberated from ‘the reality’ and I experiment with the visual image and quality of paint.

With Past Imperfect and the other works in this series, I was thinking about notions of cultural dislocation, cultural dissonance, nostalgia for the places of your childhood that you are no longer tethered to, as well as family connections and relationships. I find that working in series allows for more unconscious or accidental elements to emerge in the painting, and for experimentation on different types of separation between layers, which could have a really big impact – especially in terms of how I think about the materiality of the paint and the relative intensity of the imagery.

What is the relationship between art and psychology?

My work is driven by subject matter that relates to me, that is about my experience, childhood, nostalgia, memories that are at best fragmented in building up one’s history and identity, and how one who constantly moves around or whose situation is fluid, resolves feelings of visibility and invisibility.

I consider notions of conceptual layering of time and of navigating unstable and changing positions of self. Yet, one cannot refer to memory without also giving agency to a higher sense of self. The essential element in my work is therefore a sense of self. The psychology of self be it self-identity, collective social or cultural identity, or national identity is a widely explored theme in contemporary art.

Out of all your paintings, which has been your favourite to work on, and why?

My favourite painting to have worked on is probably Another Place and Nowhere. It’s through resolving this piece that I really started thinking about painting as a language and how it related to my diverse personal history. My painting started to lose its sense of naturalism and from there it opened different possibilities of ways of working.

My work layers the ideas of memory with the ideas that appearances in particular the archive of family photographs can be deceptive and thus posing the question of whether we can ever see things as they really are. In Another Place and Nowhere I’m also working through concerns that are relevant to post coloniality, namely a sense of loss, cultural hybridity, an ambivalent place attachment and a yearning to belong, which I think this painting captures.

If you could spend a day with an artist, dead or alive, who would it be, and why?

I contextualise my work by looking at what other contemporary artists are doing in approaches to imagery and painting. I look at artists who speak from their own experience to see and understand potentially different ways of exploring one’s internal word. I believe Peter Doig, originally from Scotland, is a great example of how his work is a palimpsest of his varied lived experiences in the UK, Canada and Trinidad. His work is often based on his memories and feelings of belonging/ unbelonging often meshing imagery from multiple sources - film, art, and literary references such as found images of Japanese ski resorts or stills from Japanese films - to create an imagined homeland.

I often use theatricality as a way of creating narratives for my groups of people. In this I am very much influenced by Walter Sickert who in his later career mainly painted from found images such as old prints, news photos and snapshots, combining the use of modern technology -photography and popular culture – with the theatre. Painting from photographs inspired Sickert to experiment more freely with visual language, which is what I am interested in.

What has been your greatest achievement so far as an artist? What are your future aspirations?

At the start of 2023, I was only part way through my Masters in Fine Art, dealing with debilitating autoimmune health issues, and wondering whether I should or could continue with my studies. Then, I was selected for the Contemporary Art Collectors Emerging Artist 12 month Programme which selects 20 artists internationally each year! It was such a boost for me and shortly after that, one of my paintings was shortlisted for Jackson’s Painting Prize, another was awarded an Honorable Mention in the Contemporary Expressions Award 2023, and I was longlisted for the Contemporary British Painting Prize. I have also just been awarded the Arts Society Chichester Research Prize 2024 which I am thrilled about particularly with my intention to take my studies forward to MPhil.

I think making submissions are an important part of one’s practice as an emerging artist, which help you to really consider what your work and practice is about. Yes of course, these acknowledgements and awards really supported me, and my partner also really encouraged me to keep going. I decided in 2024 to focus on developing my practice in my studio whilst continuing to deal with ongoing health issues which is isolating. Ultimately, I think my greatest achievement is that I have found the resilience and can believe in myself as an artist and that I am discovering who I am and what I have to say!

My future aspirations? Loads! I start the TURPS Correspondence Course in September, and I am contemplating advancing critical perspectives of the contexts I explore through applying for an MPhil. Online artist development platforms have emerged which I believe offer valuable access to resources including artist talks, skills, knowledge and context development. I want to give a shout out to Contemporary Art Academy and The Essential School of Painting whose professional and practice development online courses have really supported me recently. I feel the opportunity to connect with a community of practitioners and peer to peer engagement is an essential piece of professional development.

Why do you think art is important to society?

People have recently discovered figurative cave art that dates back some 50,000 years on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia. Imagination and storytelling, documenting social and cultural history, records of people that once lived, depicted in their culturally aesthetic ways, are why I believe art is important to society.